Appraising Ethnographic Art

Ethnographic tribal art is not something new, haphazard, or primitive, as it is called is considered non-western art from peoples who live in villages or tribes and have a hierarchical society based on clans with local chiefs. I am focusing here on African and Oceanic art, not American Indian or Pre Columbia art, each of which needs its own essay to cover. The art of Africa is vast in style and form, and as the 2nd largest continent in the world, there are about 1000 different languages spoken. To complicate things, there are areas of specialization within tribal art. For example someone who is an expert on the Congo may not know how to classify East African artifacts. Oceanic art also covers an immense area and consists of islands in Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia and Indonesia. Similarly to Africa, these peoples engaged in ancestor worship, taught their youth, and held order through specific societies and accompanying ceremonies, all of which needed artifacts to be used. Thus the art was produced for functions and was based on previously established cannons of style and form. The user/viewer all recognize the meaning of the work as it was being used. Problems arise with appraising in this field as the items are taken out of their original context; sometimes restored, conserved, and altered, so many factors such as condition, provenance, and quality affect value.

Definition

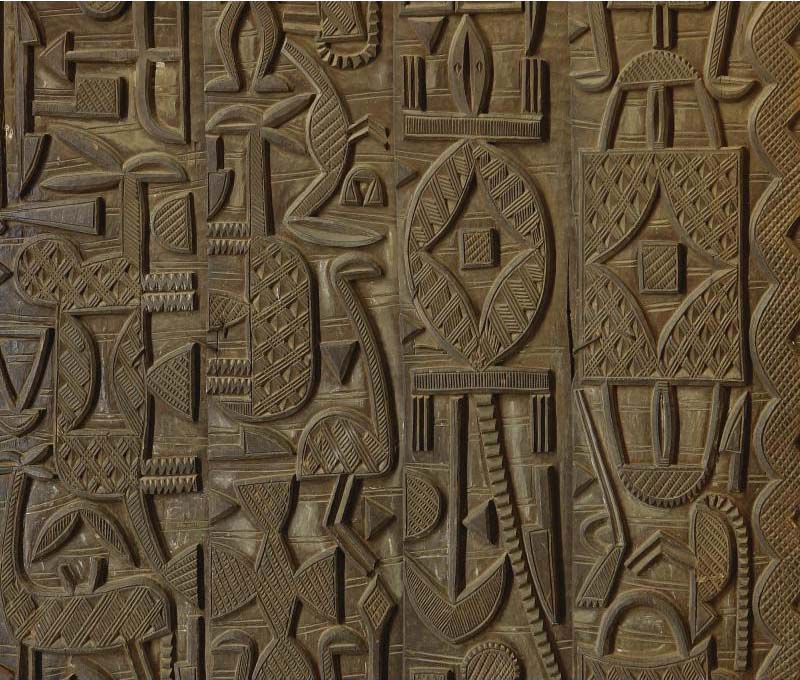

Ethnographic art is mostly made of wood and characterized by its geometric shapes and strongly abstracted representational forms and designs.

Primitive art was appreciated for its own sake in Europe at the turn of the 20th Century, where the avant-garde in Paris coveted it tremendously, and it is no secret that it directly influenced cubism. L. Segy wrote; “that we have an emotional need to respond to ethnographic sculpture because it embodies an intense emotional life. To the extent that we feel its reality, that we sense the radiations of its emotional vigor, we gain the sensation of fulfillment, of nourishing something starved in ourselves”. From a modern standpoint, the expression can be powerful and moving, and this is what gives it value. An antique, well-rendered, large carving that represented a powerful spirit that would have played a key role in the day to day lives of the people it was made for will have a substantial value. Newer, colorful, decorative, and utilitarian items all have a lesser value.

Tribal art from African and Oceania can be historically significant. Early contact between Africa and the west came in the 16th Century, through missionaries in the Congo. Because a large ocean contributed a great degree of separation to Oceanic Islands, they remained isolated from the west and from each other for most of their histories and were able to develop fairly individualistic styles and forms. Animism, the worship of spirits and fetishism, the belief in instilling supernatural powers into a man made objects are two major themes in ethnographic art.

Devoid of writing communities would communicate through the iconography and meaning of visual forms. Villages were known for certain markings so when a member traveled, one could know when boundaries were crossed and a new territory was entered when the style became different. Oral tradition was one way to tell convey knowledge, another was to carve narratives into architectural elements, figures, totems, doors. It was not until the last hundred years that ethnographic cultures melded with traditional western culture and values, themes, religions, and social and political systems were affected As societal tribal structures fade away so does their rituals and the accompanying trappings.

History

From the Sahara to the Cape, African Neolithic man created tens of thousands of beautiful engravings and paintings on the rock walls of caves and shelters dating to about 8000 to 6500 BC. The Nubians were indigenous peoples occupying a large part of the upper Nile valley. They had a great civilization before the rise of Pharaohonic Egypt where they were assimilated. The next oldest sculptural traditions in Africa are also from the western Sudan in the inland Niger delta. There were great trade routes in this area going back to 2000 BC for gold, ivory, and salt, and the natives started to embrace Islam in the 14th Century AD. In Nigeria, the Nok culture is considered the earliest lost African civilization. The large elongated abstract figures made of grog and iron rich clay TL test to 500 BC - 200 AD. These figures were discovered within the last 100 years by tin miners, and archaeologists have trouble pinpointing their origins because they have migrated due to floods and alluvial washes. None of the figures have been found in their original settings and they are considered to be patrimony unprovenanced objects. Sculptures in the area of Jenne date from 1000 to 1300 AD and the style is similar to that of the local Dogon in Mali with the elongated bodies and bullet shaped heads.

In the 16th Century, there are prized Sherbro-Portugese Ivories arising from trade. The Akan of Ghana are an old African tribal group who are especially famous for their small cast copper and bronze gold weights that come in all forms, from animals, to fruits, to abstract geometric shapes. In Africa, dress was another way to signify tribal hierarchy. Many elaborate patterned bold and graphic textile compositions were created to distinguish the upper class and rulers. One of the largest kingdoms, the Asante, is famous for its ceremonial stools and chairs that symbolize power and organization.

In the Niger Delta and the Cross River, the bronze casting tradition dates back to the 9th Century AD. The important images of Kings, portraits, Oni's, plaques and shrine pieces are well known to everyone. One of the most famous cultures is the Benin from Nigeria. Their bronze casting tradition was perhaps at its height in the 15th and 16th Centuries. The works were produced for the power of the Oba or King and may have had magical powers. Most of these early castings are now in museums.

The Largest tribe in Africa is the Yoruba, who number over 12 million peoples. They are primarily from South West Nigeria. Traditions for there artistic development go back around 1000 years and some feel there is a direct correlation between them and the Nok people. Their distinct artistic style grew out of socio-political and religious organizations within chiefdoms and under the rule of a divine King or Ife. Considered to be some of the finest output in all of Africa, bronzes of very refined Ife sculptures, dating back to the 12th Century, were found in Yoruba shrines.

Age/authenticity

It is very difficult to judge age/authenticity of Ethnographic art. The styles can have remained the same for hundreds of years but earlier examples can be archaic while later ones more baroque. Natural elements such as wood and fiber can not last long in native environments which makes the output new in relative terms; most items are younger then 150 years, so we have trouble testing it scientifically. If the item is a mask and you hold it up to your face, can you see through the holes? Is there wear where it touches your face? What kind of wood is used? Skilled carvers making important objects would use hard woods. If there are nails, are they hand forged? Based on numerous interpretations, one finds the best way to grade the work is by developing a system in which there are various degrees of authenticity. When evaluating a tribal piece for correctness, try to go at it with a critical eye. The older pieces are usually finer in details, so take time and study the ears, eyes, hair and overall form for quality. Provenance becomes important because it establishes a time line for which the collection history of the piece was initially written down. Train your eye to recognize correctness of form with the visual images in books. African Art in American Collections by Robins & Nooter is a must have book as it has thousands of images catalogued. Keep studying, go to museums and galleries and auctions and handle the objects when possible. The fact that a form is foreign, powerful, puzzling and abstract might be a sign of a pure correctness.

Just a quick mention on function and usage which may help you distinguish copies from really used examples. These peoples engaged in ancestor worship and carved figures to pay homage to deceased relatives. They engaged in Deity worship and thus used carvings on altars for prayers and favors. The carving also taught their mythology; their philosophical concepts; an example of this being totemism, which relied on animal or heraldic symbols. They engaged in divination, a practice which embodies spirits and finds messages in everyday objects. Social justice was established through the use of thrones, staffs, and textiles. Initiation and secret societies would use costumes and masks for education and social order. Music was a rich part of their lives so harps, whistles, drums and gourds were heavily utilized. Textiles, clothing and fabric were used to convey rich visual communication through the use of elaborate patterning.

Patina is the surface wear for used items over time. Look for variations to the surface from scratches to losses to oxidation to subtle discolorations. Try to understand the usage of the item; as different patinas can occur. For example, a sacrificial patina should be dried and encrusted. Wood can naturally darken, wear, chip and succumb to natural elements like moisture and insects. Natural oils in our skin transferred through touch can turn a surface smooth. In order to give pieces a dark black surface, a forger may use smoke or stains or chemicals such as potassium permanganate. Hold the piece to your nose and see if there is a smell. Does the patina rub off easily? Does the item have wear patterns that are consistent with the type of use? For example, if the piece was traditionally used in a procession, is it worn where the piece would have been picked up? If it is a mask, the back of the mask should not have the same finish as the front? The back should have soft edges and a radiating discoloration where it has been worn. All attachment holes should not be uniformly perforated around the edges.

There are a number of artificial ways to age pieces. Objects can be deliberately exposed to the elements to induce weathering. Objects can be placed in insect and termite infestations to cause damage and disintegration. They can be left to be pecked at by chickens. The can be buried and rediscovered. Patinas and sweat marks can be falsified, although the latter is not easy. Native mends are common, and fiber wears out quickly so edging is replaced often and can be newer then the wood to which it is attached. Native repairs can be clever attempts to throw you off.

Early art from the pacific was carved with stone adzes as opposed to metal blade tools. It can be recognized by with subtle waves to the woods surface which was made by the stone tool. It may look like rougher cuts up close.

Provenance

Provenance is the ongoing scholarly research investigating the ownership history. Complete provenance of a given work of art, particularly one pre-dating the nineteenth century and the advent of the modern art market, is often difficult if not impossible to establish. Information is sometimes withheld by dealers and auction houses at the request of previous owners who wish to maintain their anonymity. Established provenance can help date when a piece was originally acquired. Ideally with tribal art, if the collector was an anthropologist, or a person with the foresight to take notes on the names of the village, parties involved, and cultural context in which the item was used and the circumstances in which it was acquired, then all the better. This adds to the appeal and, probably, the value of the piece. If a collection is known to be specialized in only one area or theme, then the chances of fakes is reduced; presumably the collector really knew about what he/she was acquiring, which makes provenance particularly valuable.

Published objects are always sought after because they are usually catalogued by scholars, and the publications are usually peered reviewed. Since today’s forgeries are so good, it makes sense to consider the collection history of an object as well as the object. Provenance does add to the price of a piece during resale.

Valuation

To add to the dilemma in assessing African art, admitted copies of traditional sculpture are made all over Africa. Marshall Mount writes, “Several museum workshops and schools specialize in copying traditional art. Students at the Maison des Artisanants, a school allied with the museum in Bamako, Mali, are taught to copy some of the old sculpture styles of former French West Africa. The artists today use traditional materials and techniques in an attempt to simulate the form and finish of the original objects”. This is scary when these excellent copies are unleashed into the western marketplace.

A scholar, Dr. Roy Sieber has outlined the following rating scale for authenticating tribal art. He states: The highest values can be given to authentic tribal pieces used in tribal ceremonies that are of the highest quality. High value can also be given to objects with some age but even newer pieces if they embody a spiritual dimension. Lesser value can be given to “B Grade Authentic” – which is an authentic tribal piece diminished some by condition issue, newness, or style and lack of quality or artistry.

Next is decorative value or newer pieces – still good quality, but sometimes copies, most often a continuum of an established and traditional tribal piece but with an incorrect patina. “Airport” or tourist art (souvenirs) is generally of the lowest grade and are uninspired copies made in great quantities and have little to no value. Handicrafts are on this level also. Today’s art made from these once ethnographic areas to be sold to foreigners is not necessarily tribal. It could be considered folk art or contemporary art and has a different value scale entirely.

It is a wise idea to identify a group of specialists that can help evaluate any items you are working with. Remember that specialization in ethnographic art can be down to the tribe/culture level. In time and with experience; a dialog between yourself and the object may lead you to an answer to its authenticity but understand that in today’s world there can be various degrees of authenticity and evaluating the art in monetary terms is no easy task.

Examples illustrated of Forgeries

Kuba Cup - These cups were highly prized and used for drinking. This one only has a slight depression on top and could not really hold liquids.

Mossi Mask – The front and back surfaces of the mask are the same here, which they should not be.

Yaka Figure – The figure here is tricky as it has a missing feather and looks used, but the surface has an artificial treatment to age it, and the patina is totally even colored.

Bibliography General

Tribal Art: the Essential World Guide, by Miller, Judith, 2006, Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd.

Bibliography for African Art

African Art: an Introduction by Willett, Frank, 1971 Oxford University Press.

African Art in Transit (Cambridge Studies in Social & Cultural Anthropology), 1994 Cambridge University Press.

African Art: The Years Since 1920 by Mount, Marshall, 1988, Da Capo Press.

African Art in American Collections Survey 1989 by Robbins, Warren M. & Nooter, Nancy Ingram, 2004, Schiffer Pub Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania.

The Tribal Arts of Africa: Surveying Africa's Artistic Geography, by Jean-Baptiste Bacquart, 2002, Thames Hudson Ltd, United Kingdom.

Oceanic Art

Arts of the South Seas: Island Southeast Asia, Melanesia, Polynesia, Micronesia, The Collection of the Barbier-Muller Museum, Newtwon, Douglas ed, 1999, Prestel Publisher, Lakewood, NJ

Arts of the South Seas, by Linton, Ralph & Wingert, Paul, 1946 Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Art of the Pacific, by Brake, Brian & Simmons, D.R. & McNeish, James, 1980 H Abrams, in association with Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council of New Zealand.

Crocodile and Cassawary: Religious Art of the Upper Sepik River, New Guinea, by Newton, Douglas & Boltin, Lee, 1971, The Museum of Primitive Art, New York.

Oceanic Art, by Meyer, Anthony J. P., 2000, Konemann, Columbia, New York.

New Guinea Art; Masterpieces from the Jolika Collection of Marcia and John Friede, by John Friede & Greg Hodgins & Philippe Peltier, 2005, Five Continents & De Young Museum, San Francisco.

The Arts of the South Pacific, by Guiart, Jean; 1963, Golden Press, New York, part of The Arts of Mankind series edited by Andre Malraux & Georges Salles.

The Sculpture of Polynesia, by Wardwell, Allen, 1967. South Pacific, Art. The Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Primitive Art, NY.

Indonesian Primitive, by Hersey, Irwin, 1991, Oxford University Press, USA.

Recommended websites

www.atada.org (The Antique Tribal Art Dealers Assoc, Inc.)

www.artforeternity.com

www.tribal-art-auktion.de

Leave a comment