Collecting African Tribal Art

There is no question that traditional African art is beautiful to behold, highly prized, and valuable in today’s society. But why? How? African art raises so many questions because its forms and compositions are so very different from those of western society; it simply takes time to get used to and understand them.

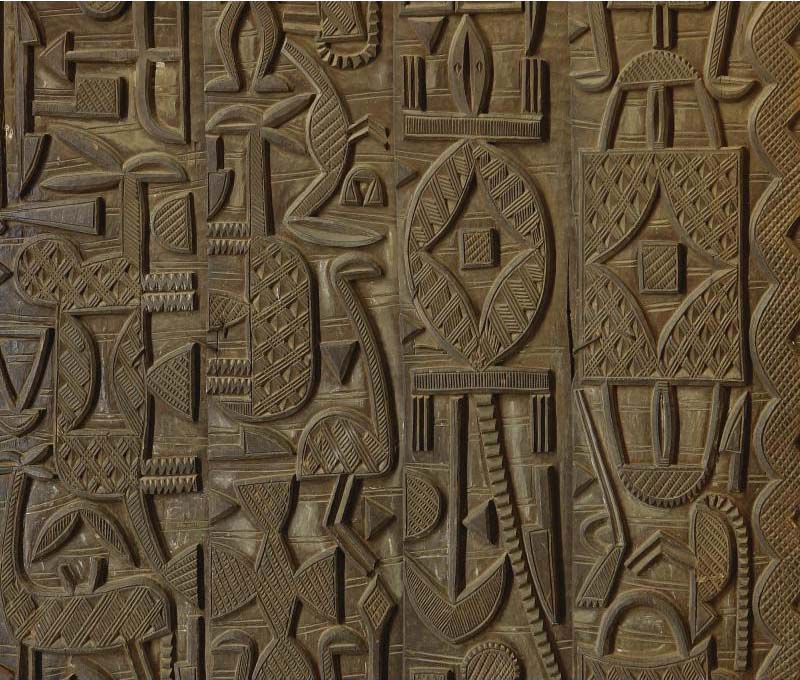

African art is characterized by its geometric shapes and strongly abstracted representational forms and designs. The architectonic masses have powerful solid and somber qualities. From a modern standpoint, the expression can be serene and moving.

Understanding tribal art takes an open mind. The aesthetics that please a tribesman can be at odds with those we consider beautiful. For example, an African woman will file her teeth to create jagged edges or stretch her neck with iron rings to look more beautiful, while we in America may consider this vulgar. Scarification, tattoos, body piercing have always been artistic expressions in African society whereas body art has, only in the last generation, caught on in the US. Perhaps to better appreciate African art, we should better understand its historical context and setting, as well as the cultural and societal forces at work, least of which are function and religion.

Traditional African art can be ancient. It also played a highly important social and religious role in African culture. The art was both functional and religious and existed in a reality totally devoid of western man. Early contact with west came in the 16th Century, through missionaries in the Congo. For the most part, the art remained mostly tribal and only watered down during colonization. It was not until the last hundred years that tribal culture melded with traditional western values, themes, religions, and social and political systems. Countries regained their independence in the 1950s, but the societal tribal structure is fading away, along with the carvings used in rituals.

African art can also be appreciated independently and without any references to its origins. This way, the feeling it evokes is based solely on its strong presence and how it makes you feel and what it makes you think. African art was appreciated for its own sake in Europe at the turn of the 20th Century, where the avant garde in Paris coveted it tremendously, thus directly influencing cubism with its simplified use of planes and forms.

Segy writes, “In our emotional need we respond to African sculpture because it embodies an intense emotional life. To the extent that we feel its reality, that we sense the radiations of its emotional vigor, we gain the sensation of fulfillment, of nourishing something starved in ourselves.”

Background

The huge diverse continent of Africa with its mountains, jungles, deserts, wild life, rivers, and vegetation has great variety of artistic expression. There are over 800 languages alone and the continent is 3 times the size of the United States. African art is generally broken down into various geographical regions, each with its own sub-specialties and nuances of style. For many, the study of African art is a life long pursuit and requires focus and specializing. Just because someone is an expert on the art in the Western Sudan does not mean that they know about the art of Tanzania in the East.

The Beginnings

From the Sahara to the Cape, African Neolithic man created tens of thousands of beautiful engravings and paintings on the rock walls of caves and shelters. They depicted a variety of scenes with figures, animals, and cosmologies, dating to about 8000 to 6500 BC. The Nubians were indigenous peoples occupying a large part of the upper Nile valley. They had a great civilization before the rise of Pharaonic Egypt where they were assimilated; their artistic styles were later subjugated to the canons of Dynastic Egypt, then the Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines and finally the world of Islam.

The next oldest sculptural traditions in Africa are also from the western Sudan in the inland Niger delta. There were great trade routes in this area going back to 2000 BC for gold, ivory, and salt, and the natives started to embrace Islam in the 14th Century AD. In Nigeria, the Nok culture is considered the earliest lost African civilization. The large elongated abstract figures made of grog and iron rich clay TL test to 500 BC - 200 AD. These figures were discovered within the last 100 years by tin miners, and archaeologists have trouble pinpointing their origins because they have migrated due to floods and alluvial washes. None of the figures have been found in their original settings. These exciting sculptures demonstrate that strong abstract figural representation has been an artistic sculptural tradition in Africa for 2500 years. African art is not something new, haphazard, or primitive. Sculptures in the area of Jenne date from 1000 to 1300 AD. The style is similar to that of the local Dogon in Mali with the elongated bodies and bullet shaped heads. In the 16th Century, there are prized Sherbro-Portugese Ivories arising from trade.

The Akan of Ghana are an old African tribal group who traded with Muslims. The Akan were skillful with weights. They are especially famous for their small cast copper and bronze gold weights that come in all forms, from animals, to fruits, to abstract geometric shapes. In Africa, dress was another way to signify tribal hierarchy. Many elaborate patterned bold and graphic textile compositions were created to distinguish the upper class and rulers. One of the largest kingdoms, the Asante, is famous for its ceremonial stools and chairs that symbolize power and organization.

In the village of Igbo-Ukwu in the Niger Delta and the Cross River, the bronze casting tradition dates back to the 9th Century AD. Bronze casting is a sophisticated means by which African artists expressed themselves. The important images of Kings, portraits, Oni's, plaques and shrine pieces are well known to everyone. One of the most famous tribes is the Benin from Nigeria. Their bronze casting tradition was perhaps at its height in the 15th and 16th Centuries. The works were produced for the power of the Oba or King and may have had magical powers.

The Largest tribe in Africa is the Yoruba, who number over 12 million peoples. They are primarily from South West Nigeria. Traditions for there artistic development go back around 1000 years and some feel there is a direct correlation between them and the Nok people. Their distinct artistic style grew out of socio-political and religious organizations within chiefdoms and under the rule of a divine King or Ife. Considered to be some of the finest output in all of Africa, bronzes of very refined Ife sculptures, dating back to the 12th Century, were found in Yoruba shrines.

Usage

As the name suggests, tribal art is just that: art born from settled farmers and hunters with Kings, wise men, elders, secret societies and rites. Devoid of writing, African art communicates through the iconography and meaning of its visual forms. Villages were known for certain markings so when a member traveled, one could know when boundaries were crossed and a new village was entered. Oral tradition was one way to tell a story, whether the history of a kingdom or the origins of mankind. These allegorical stories were carved as narratives into doors and architectural elements to educate the people.

The traditional art consists of wood carvings, both masks and sculpture, stone carvings, architectural elements, furniture, pottery , which was mostly done by females, metalworks in the form of currencies, bracelets, weights, weapons, pipes, textiles, and beadwork and weavings.

Tribes & peoples:

In the Western Sudan

Niger Delta; Nok, Sokoto, Katsina, Bura. In Mali; Jenne, Dogon, Bamana, Songhai, Segu Style, Marka, Bozo. In Burkina Faso (Upper Volta); Kurumba, Nuna, Bwa, Ko, Bobo Mossi, Lobi, San, Toussian. Western Coastal Region; In Guinea; Baga, Landuman, Nalu. In Sierra Leone; Kissi, Sherbro, Sapi, Mende, Nomoli, Limba, Temne. On Bissagos island; Bidjugo. In Liberia; Dan, Sapi, Bassa, Toma, Loma, We, Grebo.

On the Ivory Coast

We, Grebo, Guro, Kulango, Ligbe, Baule, Bete, Nafana, Dagarti, Dabakala, Senufo, Attye, Anyi. In Ghana; Akan, Asante, Fante, Moba (Togo). In Republic of Benin; Fon, Edo, Royal Benin.

In Nigeria; Yoruba, Owo, Esie, Igbo, Urhobo, Ijaw, Abua, Isoko, Ibibio, Oron, Ijo, Ogoni, Eket, Idoma, Igala, Tiv, Afo. In Northern Nigeria; Boki, Along the Cross River; Anyang, Widekum, Ejagham, In the Benue River Area; Chamba, Mumuye, Jukun, Nupe. In Chad; Bagirmi.

Western Central Africa

In the Northern Cameroon; Mambila. Grassfields Cameroon; Tikar, Tigono, Bafo. Central Grassfields; Bamun, Wum. Southern Grassfields, Bamileke, Baham, Babanki, Cameroon Highlands; Kom; Southern Forest; Duala.

In Gabon; Fang, Mvai, Betsi, Bieri, Kota, Sango, Mahongwe, Kwele, Mbete, Tsogo, Vuvi, Puna, Ogowe River Groups, In Republic of Congo; Kongo, Bwende, Kugni, Yombe. In Central Africa, In Republic of Congo; Bembe, Tsaye, Teke, Kuya, Hungana, Bangi.

In Zaire and Angola; Pende, Eastern Pende, Yaka, Lega, Mbole, Siki, Mbala, Kwese, Suku, Woyo, Vili, Yombe, Tsotso, Mangbetu, Mbagani (Chokwe influence) Lwalwa, Salampasu, Lele, Kete, Biombo, Kuba, Ikula, Tswa, Dengese, Kanyok, Binji, Nsaponsapo, Luba, Hemba, Zela, Kusu, Songye, Pere. In Angola; Ovimbundu, Songo, Lwena, Chokwe, Katanga. Ubangi River Areas, Zula, Tabwa, Tetela, Holoholo, Boyo, Ngombe, Ngbaka, Boa. In Northern Zaire; Zande.

Eastern Africa

In the Sudan, Kushite, Bija, Bongo, Shilluk, Omdurman, Konso, In Ethiopia; Gurage, Addis, Ababa. In Somalia; Merca. In Kenya; Kamba, Giriama, Turkana. In Tanzania; Jiji, Nyamwezi, Makonde, Maasai, Mbulu. In Mozambique; Makonde, Maravi, Chemba, Bisa, Noyonanyonga.

South Africa

Zulu, Nguni, Tembu, Ndebele, Malagasy, Sakalava, Mahafaly. Zambia; Rotse, Lozi. Zimbabwe; Shona.

Themes & Concepts:

Animism

Dolls

Fetishism

Missionary Art

Magic Art

Function & Usage

Ancestor worship - Use of carved figures to pay homage.

Mythology – represent philosophical concept

Deity Worship - Use of carved figures, magic and altars to pay homag

Divination – to embody spirits and find messages in everyday objects.

Social Justice – Thrones, staffs, textiles.

Totemism – Animals or heraldic symbols.

Secret Societies - Use of carved masks, rites and trophies for reward.

Initiation Rites – Use of carved masks in education.

Rank – Use of furniture, sculpture, textile and architecture to establish.

Music – Harps, whistles, drums, gourds.

Textiles – Clothing, fabric and panels which conveys rich visual communication through patterns.

Authenticity

When evaluating a tribal piece for correctness, try to go at it with an experienced eye. The older pieces are usually finer in details, so take time and study the ears, eyes, hair and overall form for quality. The fact that a form is more foreign, powerful, puzzling and abstract might be a sign of a purely correct piece. Train your eye with the visual images in books. Breaking down a three dimensional work in a two dimensional media brings everything to the picture plane on the page. Such an exercise should inform what proper proportions and representations are. Keep studying, go to museums and galleries and auctions and handle the objects when possible.

Patina is surface wear over long periods of time. Wood can naturally darken, become smooth and build up a shine from natural oils in our skin transferred through touch. In order to give pieces a dark black surface, a forger may use smoke or stains. Hold the piece to your nose and see if there is a smell. Does the patina rub off easily? Does the item have wear patterns that are consistent with the type of use? For example, if the piece was traditionally used in a procession, is it worn where the piece would have been picked up? If it is a mask, the back of the mask should not have the same finish as the front. All attachment holes should not be uniformly perforated around the edges, and there should be areas of discoloration where the mask was in contact with the face.

There are a number of artificial ways to age pieces. Objects can be deliberately exposed to the elements to induce weathering. Objects can be placed in insect and termite infestations to cause damage and disintegration. They can be left to be pecked at by chickens. The can be buried and rediscovered. Patinas and sweat marks can be falsified, although the latter is not easy. Native mends are common, and fiber wears out quickly so edging is replaced often and can be newer than the wood to which it is attached. Native repairs can be clever attempts to throw you off.

To add to the dilemma, admitted copies of traditional sculpture are made all over Africa. Marshall Mount writes, “Several museum workshops and schools specialize in copying traditional art. Students at the Maison des Artisanants, a school allied with the museum in Bamako, Mali, are taught to copy some of the old sculpture styles of former French West Africa. The artists today use traditional materials and techniques in an attempt to simulate the form and finish of the original objects”. This is scary when these excellent copies are unleashed into the western marketplace.

Dr. Frank Willet writes,” The most obvious authentic works on which all would agree are those made by an African for use by his own people and so used. However, this category can be subdivided into those of superior, average, or inferior aesthetic quality. A little lower on the scale is a work made by an African for use by his own people but bought by an expatriate before use. Then comes sculpture made by an African in the traditional style of his own people for sale to an expatriate; then made by an African in the traditional style on commission by an expatriate; then sculpture made by an African in poor imitation of the traditional style of his own people for sale to an expatriate; made in the style of a different African peoples (though it may be well done) for sale to an expatriate; made by an African in a non-traditional style for sale to an expatriate. Finally we have works made by an expatriate, i.e. non-African, for sale to other non-Africans but passed off as being African. (The last one is considered totally fake).

In time and with experience; a dialog between yourself and the object may lead you to an answer to its authenticity but understand that in today’s world there are various degrees of authenticity.

It is a wise idea to identify a group of specialists that can help vet any new acquisitions to your collection. Remember that specialization in African art can be down the tribe/culture level.

On Provenance

Provenance is the ongoing scholarly research investigating the ownership history. Complete provenance of a given work of art, particularly one pre-dating the nineteenth century and the advent of the modern art market, is often difficult if not impossible to establish. Information is sometimes withheld by dealers and auction houses at the request of previous owners who wish to maintain their anonymity. Established provenance can help date when a piece was originally acquired. Ideally with tribal art, if the collector was an anthropologist, or a person with the foresight to take notes on the names of the village, parties involved, and cultural context in which the item was used and the circumstances in which it was acquired, then all the better. This adds to the appeal and, probably, the value of the piece. If a collection is known to be specialized in only one area or theme, then the chances of fakes is reduced; presumably the collector really knew about what he/she was acquiring, which makes provenance particularly valuable.

Published objects are always sought after because they are usually catalogued by scholars, and the publications are usually peered reviewed. Since today’s forgeries are so good, it makes sense to consider the collection history of an object as well as the object. Provenance does add to the price of a piece during resale.

Quality Rating Scale

The quality rating scale used here is that of Dr. Seiber and is as follows:

1. Authentic tribal pieces usually used in tribal ceremonies. The highest rating for authenticity and quality – usually with some age but even newer pieces if authentic and embodying a spiritual dimension.

2. “B Grade Authentic” - Same as 1 except diminished some by condition, newness, or style and quality of the artist’s effort.

3. Decorative newer pieces – still good quality, but sometimes copies. Most often a continuum of an established and traditional tribal piece but with an incorrect patina. Decorative value.

4. African arts made to be sold to foreigners – Europeans, Americans, and others. Not necessarily tribal, could be folk or contemporary.

5. “Airport” or tourist art (souvenirs). Lowest grade and made in great quantities.

Enjoy African art for its historical significance. Enjoy the power of the forms and designs as they move you. One can gain such personal satisfaction and accomplishment with the formation of a collection. Because tribal art is very geometric and exists strongly in a three dimensional space, it is very much up front : its presence can be awe inspiring. Early collectors thought the art was crude and primitive, yet today we understand that the forms and styles in African art are exactly the way the artists chose to represent them. Strong, focused, and contemplative, tribal art nurtures our souls.

Written 1/09/2006

Leave a comment