Ancient Art ·

Antiquities ·

Babylonian ·

cuneiform ·

Cylinder Seal ·

Egyptian Art ·

Hieroglyphics ·

Hittite ·

sumerian ·

Words Pressed on Clay

An ancient Sumerian poem tells the first known story of the invention of the written word:

Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat (the message), the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

— Sumerian epic poem Enmerkat and the Lord of Aratta, Circa 1800 BC

Emerging in Sumer in the late fourth millennium BC, Sumerian cuneiform is one of the earliest writing systems, and is considered the most significant of the many cultural contributions made by the ancient Sumerians. The writing began as a system of pictograms, which, over millennia, became abstracted and distinctive. The name comes from the Latin word cuneus, for 'wedge,” referring to the blunt reeds used by ancient scribes to make the wedge shaped marks that characterize the language. All of the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform until the emergence of alphabetic script, after 100 BC.

Clay cones inscribed with cuneiform, also referred to as ‘foundation pegs’ or ‘nails’, were driven into temple and building walls. They served as evidence that the structures were the divine property of the gods and kings to whom they were dedicated. The writing on these cones lyrically describes a rich and complex ancient hi story, and reveals a sophisticated religious, technological and commercial culture.

At Art for Eternity we are proud to share two high quality examples of this ancient technology.

The Ishme-Dagan cone is buff clay, has excellent provenance and surface, and 12 columns of beautifully cut text. It is dedicated to Ishme-Dagan, 4th king of the First Dynasty of Isin, who reigned for two decades (1953-1935 BC).

‘Mighty man, king of Isin, king of the four quarters,’ the inscription reads, ‘he cancelled the tribute obligations of Nippur, the city beloved by Enlil, and excused its men from military service, he built the great wall of Isin.'

A similar piece sold at Christie’s in 1997.

Another fine example is the Foundation Cone for the Governor of Lagash , created for commemoration of the Eninnu temple of Ningirsu. Its inscription reads:

“For (the god) Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of (the god) Enlil, Gudea, governor of Lagash, a resplendent marvel, the Eninnu Temple-Brilliant Lion-Headed Eagle-he built and restored (to its former condition).”

A similar example can be seen at theDetroit Institute of Arts.

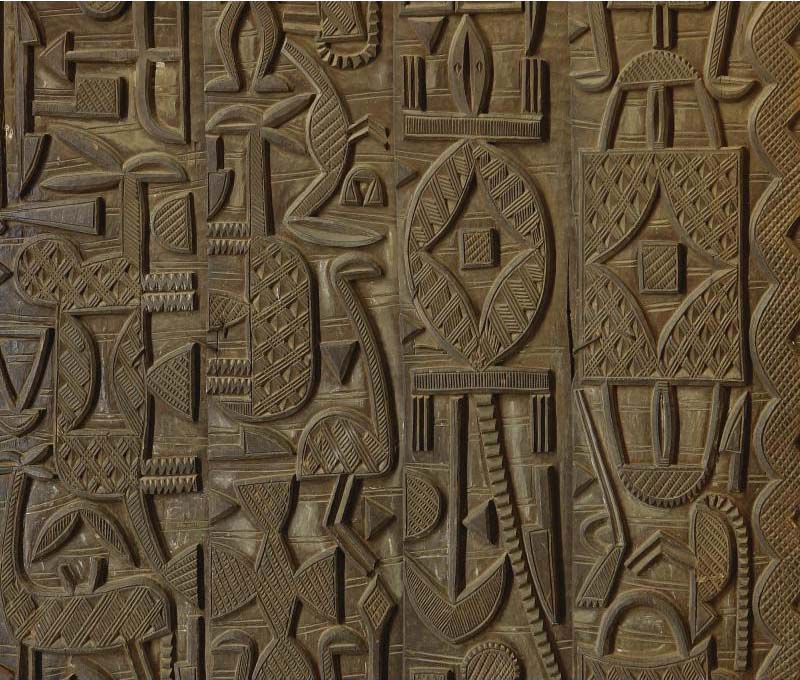

We are also proud to share another refined example of ancient writing technology: an Old Babylonian Cylinder Seal . Cylinder seals, which were used to roll impressions onto wet clay surfaces, had many functions in ancient life, from the sublime to the mundane. They were used as jewelry and protective magical amulets. They served as signatures, seals and signs of ownership. They were used to seal doors, baskets and jars. High technical and artistic skill was required to inscribe hard stone with intricate figures, text and symbols. In this fine, black carved stone example, the scenes are gorgeously composed and miraculously alive. There are three standing figures, the Sun God Shamash on the right, and a three-line cuneiform inscription. A similar example can be seen at the Met.

At Art for Eternity we are grateful to the ancient Sumerians for inventing writing, and for recording its birth. We hope you enjoy these timeless works of art, and that you enjoyed reading about ancient writing as much as we enjoyed writing about it.

Leave a comment